When teaching workshops related to portraiture or figure

painting, I often encounter artists who feel somewhat mystified by the colors

they see in skin. From a naturalistic standpoint skin follows all the rules of

physics that any other material does. So like any other material, once we have

a better understanding of skin, we can begin to demystify the colors we see.

I generally encourage the artists I work with to think in

terms of identifying a local color specific to the region of form(s) they are currently

painting. This local color can then help guide their color choices rather than their

reacting moment-by-moment to the colors they feel they see. From a somewhat

simplified standpoint I would encourage painters to consider three main

variables when accounting for the local color of a given region: (1) the

amount of blood present, (2)the amount of pigmentation, and (3) the color of the

skin itself (devoid of or with low

amounts of blood or pigmentation). There are, of course, variations between

these as we visually detect more or less of each.

In this post I will try to expand upon these variables in

order to help explain what local colors are really present in skin and why. In

subsequent posts I would like to discuss how narrow the color range of skin

really is under average lighting conditions, and also how a regional local

color, when combined with various modeling factors, gives us the full range of the

colors we experience visually when looking at flesh tones.

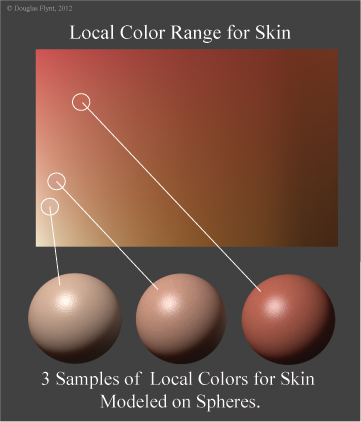

The following diagram shows a range of local skin colors in

addition to spheres illustrating the modeling factors seen for 3 different

local colors selected from this gamut.

The Local Color of

Skin Absent Blood or Pigmentation:

I want to start with a discussion of skin imagined with an

absence of blood or visible pigmentation. This concept of skin as a "local

color" stands as the blank canvas for every individual—regardless of

ethnic background. To this we can add factors of blood and pigmentation. Of

course in reality this "local color" in its most ideal state is

perhaps impossible to fully experience. Even in cases of albino individuals (illustrated in the

following images from Wikipedia[1]), who

lack any pigmentation, the blood in the skin will affect the color we see.

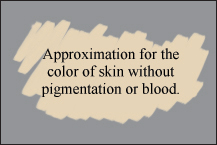

However, in order to obtain a sense of the skin color to

which I am referring, first locate a place on your body that has little visible

pigmentation—perhaps the palm of the hand, or some other area that receives

little sun exposure. This will, of course, be easier for lighter skinned

individuals. On this area apply a generous amount of pressure to displace the

blood from the region and then remove the pressure. For a brief moment, before

the blood returns, the color you observe will begin to offer a sense of the

local color we are conceiving of at it's most extreme state. Trying to classify

this color can be a bit tricky. Most scientific accounts of which I am aware

typically only say that skin by itself is yellowish in color. I would narrow

this down more by adding—from my own experience—that skin by itself is rather

light in value and more orangish-yellow rather than the yellow it is often described

as. By itself, it also generally offers the lowest chromatic intensity of any

local color observed in skin.

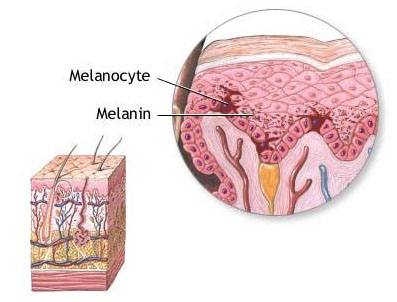

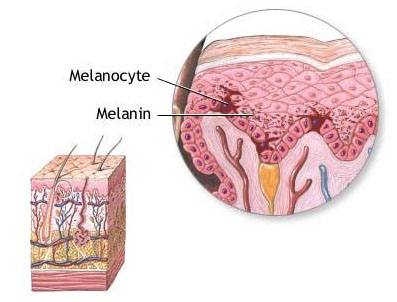

Melanin as a Pigment:

Within the epidermal, or upper layer of our skin, we find

melanocytes or cells that produce melanin. This melanin is responsible for helping

to protect us from the sun's ultraviolet rays. Although everyone, regardless of

ethnicity, has approximately the same number of

melanocytes, the production rate, size, and type of melanin pigment they

create, is what offers the visual color differences between various individuals.

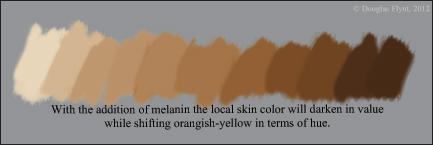

The two types of melanin produced are pheonmelanin which is

often described as light yellow, tan or even reddish yellow and eumelanin which

is alternatively described as dark brown or even black. After reviewing a

number of descriptions and various charts showing the wavelengths both types

absorb, it would appear that they show more of a marked difference in terms of

value rather than hue. The result is that, in general, the addition of melanin of

either type contributes toward skin darkening in value while shifting its hue

toward an orangish-yellow. To get a better sense of the color they contribute

try looking at moles and freckles. These can offer some sense of their color

since their appearance is brought on by an increased amount of melanin.

For each individual this melanin production will affect the

overall skin color. Additionally, within a particular individual, areas that

get more sun exposure will produce more melanin. The result is that these areas

will be darker in value than the paler skin regions with little visible blood

or melanin.

Blood and Hemoglobin:

Within our blood, the oxygen carrying protein, hemoglobin,

is largely responsible for the reddish color we see. The following photograph[2] shows human blood magnified 600 times.

In regions with larger amounts of blood present, the blood

will, of course, contribute toward shifting the appearance of the skin towards

red. Additionally, since this red is more chromatically intense than either the

color of melanin, or skin with an absence of blood or melanin, these blood rich

regions will have the highest chroma of any of our local skin colors—a

relationship that is well to keep in mind in order to produce the appearance of

naturalistic skin. It might also be speculated that since blood vessels are found

in the lower dermal layer of the skin, individuals with darker skin will not

show as pronounced of a local color shift when entering these blood regions

since the melanin causing the darker skin tones resides above the hemoglobin—somewhat

masking its appearance.

Variations:

The colors I have offered for blood, melanin, and skin

absent either, really suggest extremes. There will of course, be variations in

between them so that we may have to consider more than one to distinguish the

local color of a region. For instance, on lighter skinned individuals, the areas

that receive a fair amount of sun exposure will produce some melanin suggesting

that the region will be orangish-yellow. However, when hemoglobin is seen in

combination with the melanin, the hue's appearance will shift back toward red,

resulting in a local color that might be thought of as more truly orange in

character. The following chart shows the color of skin lacking both hemoglobin

and melanin in the lower left hand corner and the resulting color shifts as they

are both introduced. In theory, this chart should offer the full range of skin

colors found in any individual—including various local colors for a particular

individual that could be selected from within the array. Please keep in mind

that the colors selected for the chart were approximated.

Veins:

Although I did not mention veins in my introduction,

what color to use for them is often a concern that arises when discussing skin

colors and so I thought I should address it. Contrary to what is commonly

assumed, veins are not actually blue in color. These blood vessels that

generally carry deoxygenated blood back to the heart are actually very dark red

in color with some suggestions that along with this darkening of value the red

appears more purplish. The following image[3] shows venous blood—offering some sense of it's color.

Although, like Wikipedia, most sources tend to suggest that

the bluish color is "because the subcutaneous fat absorbs low-frequency

light, permitting only the highly energetic blue wavelengths to penetrate

through to the dark vein and reflect back to the viewer,"[4] I am troubled by this explanation. For a

thought exercise, let's assume a model where an even spectrum of white light is

illuminating an arm with visible veins. Now, try to keep track of the various wavelengths

that are somewhat absorbed or reflected, as the light passes through the skin

(orangish-yellow), melanin (orangish-yellow), hemoglobin (red) and possibly even

the fat (yellowish color) before it then strikes the dark but still predominately

red vein, and then passes back up through all of these materials again. Keeping

in mind that the color of an object is the result of what is reflected rather

than absorbed, the resulting wavelengths available for the viewer to see after

this journey would seem to offer a predominance of wavelengths throughout the

red, orange and yellow spectrums rather than the blues the Wikipedia quote

seems to suggest.

To complicate things further, the same Wikipedia article

cites a study entitled Why do veins

appear blue? A new look at an old question. The summary of this study

states that "the reason for the bluish color of a vein is not greater

remission of blue light compared with red light; rather, it is the greater

decrease in the red remission above the vessel compared to its surroundings

than the corresponding effect in the blue. "[5] With an understanding that "remission,"

as it relates to how light interacts with materials, means "to send

back," the first part of this summary would seem in direct contrast to the

previous quote from the Wikipedia article and somewhat closer in line to the results

of the greatly simplified thought exercise I offered. As with the second part

of the study just quoted, some sources additionally cite visual perception as

playing a role in perceiving veins as blue.

To my understanding, visual perception seems to be a more

creditable account of what is occurring. Tied to "retinex theory," a

very low in chroma reddish-orange when seen surrounded by a field of the same

color can easily be judged as bluish or bluish green in color—even though in

actuality it is not. For this reason, I often suggest that a very very low in

chroma orange or reddish-orange (the color should be more exactly determined by

the local color of the region) that is slightly darker than the surrounding

local color will often serve just fine to suggest veins.

This effect is demonstrated in the two following images: The

first shows two larger squares. The left square is reddish-orange,

approximating a skin color, while the right square is chromatically neutral. The

smaller squares, contained in each of the larger squares, are the same color.

On the left the smaller square appears slightly bluish in color while on the

right you can more accurately see it is actually a very low chromatic

reddish-orange. With finer lines, rather than squares, the effect is even more

striking as is illustrated in the second image.

Part I Summary and

Future Posts:

Thus far we have been looking at what causes the various local

colors we see in human skin. I have yet to address how narrow the color range

for skin really is under average lighting conditions (although this may have already

been inferred by the discussion offered) or how the modeling factors for these

local colors influence any additional colors we might perceive. In future posts

I hope to address both. When addressing modeling factors I will discuss

highlights, a type of specular reflection, and how, when dealing with diffuse

reflection, the loss of light on a local color offers variations of value and

chroma of that local color. Additionally, I plan to address other considerations

such as reflected light (diffuse inter-reflection) and translucency (diffuse

transmission).